Inside the Memorial Trials – “When you make fun of evil, it stops being scary”

In today’s unprecedented decision, the Russian Supreme Court has shut down the country’s most prominent human rights organisation – International Memorial Society. The organisation has been on trial since 25 November for allegedly violating the ‘foreign agents’ law, a law designed by authorities to silence critical voices and stifle civil society.

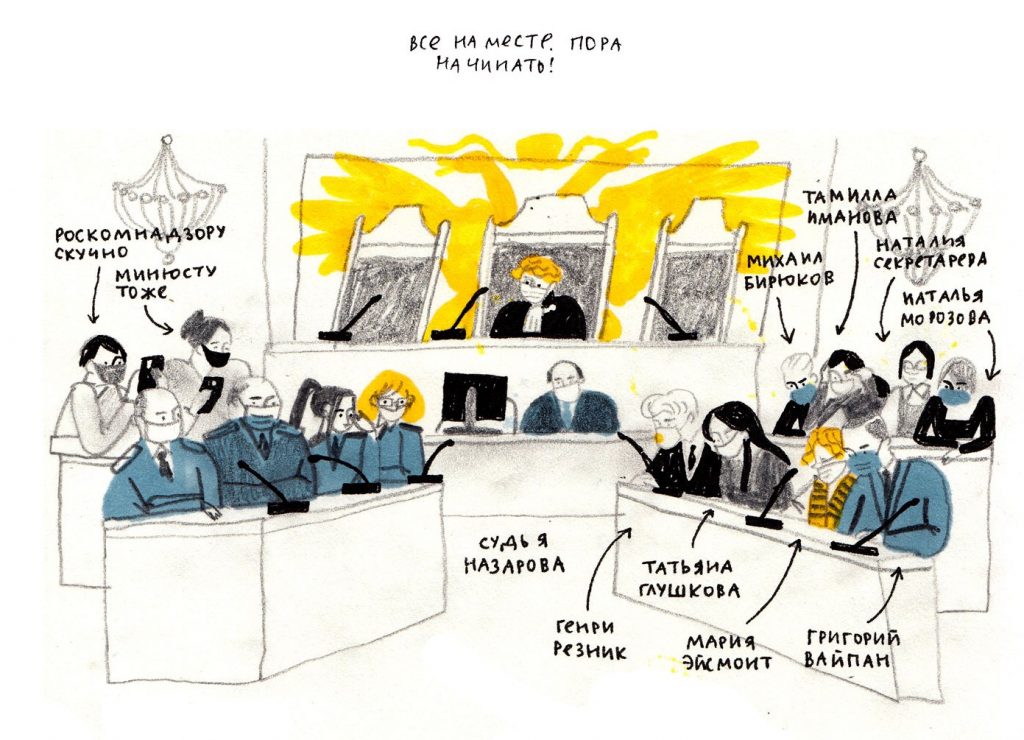

Artist Catherine Gushchina has created artwork from inside the courthouse, portraying the judge, the prosecutors, and Memorial’s lawyers and supporters present at the hearings. Her artwork, unlike classical courtroom sketches, has a strong message and emotional components, and she often combines images with texts to create an artistic narrative of the events. Civil Rights Defenders spoke to Gushchina who shared her experiences of portraying the historic hearings, and about how laughter can win over fear.

The following represents the opinion of the interviewee and does not reflect the opinions of Civil Rights Defenders or any mentioned organisations.

How and why did you decide to illustrate Memorials’ court hearings?

Gushchina: Last summer I was working on my master’s thesis, a graphic novel about the life and work of [Andrei] Sakharov. In my work, I wanted to highlight something that I had seen in Sakharov’s memoirs, that one can solve many problems by smiling, that the clouds would dissipate from laughter, that it’s important to try to treat life with irony, and this way it’d be easier to live through the hard times. People from Memorial helped me with my work, and then we organised my exhibition in Memorial’s office. When I learned what was happening with Memorial, I wanted to help.

Is this your first time working as a court artist?

Gushchina: I heard that such a practice existed, but never saw concrete examples. This was my first court. Right now, two organisations are on two separate trials, International Memorial [Society] and Memorial Human Rights Centre. I was not allowed to be present at the court hearings on the Human Rights Centre. I went there as well but had to stay outside. When the first trial on International Memorial started in the Supreme court on Arbat street, I was allowed to get in.

Does it ever get scary doing that – being inside the court, sketching the ongoing court hearings?

Gushchina: I am not scared. I think that, and it’s reflected in my drawings as well, you have to perceive the situation through the prism of humour. I even dressed up specifically for that occasion. I wore my most luxurious long black dress with puff sleeves, I put on make-up. Any court hearing is a [theatrical] stage. And this courtroom, with its huge crystal chandeliers and velvet chairs, reminds me very much of a theatre. I am not a participant, so I am trying to also be an actor, but the one in the audience. And it has been important for me to look bright and strange. I wanted the opposing side, such as the prosecutors, the Ministry of Justice, Roskomnadzor [Russia’s state media regulator], to notice me and to see that I am drawing them, and that I am looking them in the eye. I have behaved not defiantly but proudly. And this pride, this confidence, helped me to win over fear.

So, irony and humour are good weapons against fear?

Gushchina: Yes, and it is in line with my idea that I expressed in my graphic novel about Sakharov, that one must be able to laugh at evil. When you make fun of evil, it stops being scary. In my court drawings, the prosecutors’ side is illustrated as a bit dumb, lazy, brawlers. I understand that these are their masks, and I never want to offend anyone personally, but I am making fun of those masks.

In my drawings, I show this as a battle of good and bad, of “us” versus “them.” Henri Reznik [one of Memorial’s defence lawyers] is like Dumbledore, and they [the prosecutors’ side] are like Voldemorts. We even have our own Harry Potter, the lawyer [Grigory] Vaipan.

There is also an overall feeling of absurdity in all of it, from naming Memorial a foreign agent to putting it on trial and trying to liquidate it for not marking some of its [social media] posts as such [made by a ‘foreign agent’]. And because of this absurdity, I sometimes feel that in the end, the judge will just stand up, say “Happy new year” to everyone, give us some candy, and all of it will turn out to be a mistake.

Does it feel stressful at all to do this work during court hearings?

Gushchina: Yes, it does. It is actually terrifying to understand that behind all this theatricality there is real life. And when a couple of times the judge stopped the process, I felt that she might actually read the verdict, say that everything is liquidated, slam the gavel, and leave. And in these moments, I felt real terror.

Besides, it is physically hard to draw non-stop for four hours. My hands start to shake. I have to draw and at the same make time to absorb what is going on. It is a psycho-emotional strain. And once I get out of the court, I can’t relax, rather I have to continue being focused, go home or to a coffee shop, and finish the reportage, finish some of the drawings. During that time, I cannot even drink, eat, or speak with anyone, I have to carry all that information inside myself until it is published. Up until I submit the drawings, it’s very intense and hard. And after that, I just feel a huge emptiness inside.

And yet, you continue doing this. Why?

Gushchina: I understand that what is happening now is a historic event, and future schoolchildren could be reading about it in textbooks, namely about this attempt to liquidate Russia’s oldest human rights organisation. I am trying and will continue to try to help Memorial in any way I can.

What can you tell those who do not live in Russia, but who might want to support Memorial? What can they do?

Gushchina: First of all, in terms of active involvement, people have been coming out for pickets in support of Memorial in different countries around the globe. This expression of solidarity is very important. Everyone sees it, people from Memorial see it, and it makes things less scary. Any support, in fact, is important.

Secondly, you can find the way in which Memorial can be useful for you. Memorial has huge archives. It has published many books, it has a very interesting website, it has a dissidents’ archive. It might be somehow connected to you, your friends, acquaintances. If Memorial helps you somehow, then you will tell your friends about it. Try to understand what Memorial is doing. And once you understand something, it is easier to love and care about it.