Emotional Security: Voicing the Silence

At Civil Rights Defenders we have a defender-centric approach. This essentially means that we put our human rights defenders at the centre of attention for our work. We try our very best to enable them to affect their issues in their own context.

You only have to browse the news page of our website, or other human rights organisation websites, to see the pressure, threats and sometimes violence and imprisonment that human rights defenders face more or less daily. Naturally, the stress takes its toll. Hence, there has been a debate in the last couple of years about burnout and PTSD in the human rights defenders community. This is also why Civil Rights Defenders, besides providing trainings on psychosocial security, have been working on finding new smart ways to provide emotional support to our partner human rights defenders.

“I first came across the issue when interviewing human rights advocates on my podcast ‘Plurrify’. For example the human rights lawyer, Brian Concannon, who drove the case against the United Nations for spreading cholera in Haiti, mentioned how the people affected and his team needed psychological support to better handle the pressure. Or even, in the case with N-Map, how staffers covering human rights issues remotely, came to suffer from PTSD based on the material they viewed and stories they read.” — Mathias Antonsson, head of the Innovation Initiative.

At RightsCon, we took part in a discussion, headed by Witness and Physicians for Human Rights, where they highlighted the importance of, and the steps they had taken to manage stress and burnout for staff in their organisations. The organisational setup is indeed very important, and something we will highlight further below. We shall henceforth refer to issues of ‘mental health’ as ‘emotional security’.

Civil Rights Defenders, based on our defender-centric model, have focused on the human rights defenders that we work with. So, at this years Defenders’ Days, our biennual conference, we organised a survey.

The purpose was twofold; to find out if the human rights defenders we work with experience stress and/or anxiety, and if so, what support — if any — they have or wish to receive.

The survey results are disheartening. However, before we get there, we should mention who filled it out, who the respondents were. We surveyed 35 human rights defenders that attended a two-day workshop on emotional security during Defenders’ Days. As such one can argue that there is a bias and a small group of respondents.

In terms of bias, individuals that chose to participate in a workshop on emotional security are probably more likely to experience issues on the topic. You should view the results in that light. However, for our purpose this is the right target audience. If we are to launch proactive measures of support, we should target the most affected among the human rights defenders we work with, so for us, this is a positive bias.

When it comes to the amount of respondents that filled out the survey, the population sample, 35 people aren’t that many. This means we can’t draw any conclusions, to extrapolate, what these responses means for the larger community of human rights defenders. As mentioned above, we wanted to survey the human rights defenders that we work with, to see if emotional security indeed is an issue for them, and to spot trends.

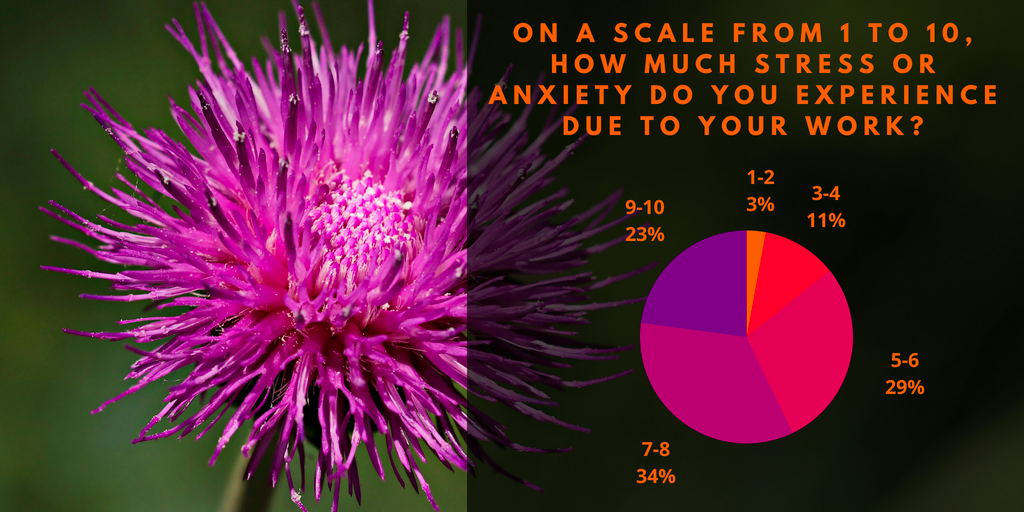

As you can tell by the above chart the vast majority experience some or much stress or anxiety due to the nature of their work. This clearly answers one of the two posed questions we wanted answered with the survey, namely, is stress and/or anxiety an issue for our partner human rights defenders? As you can tell, it clearly is.

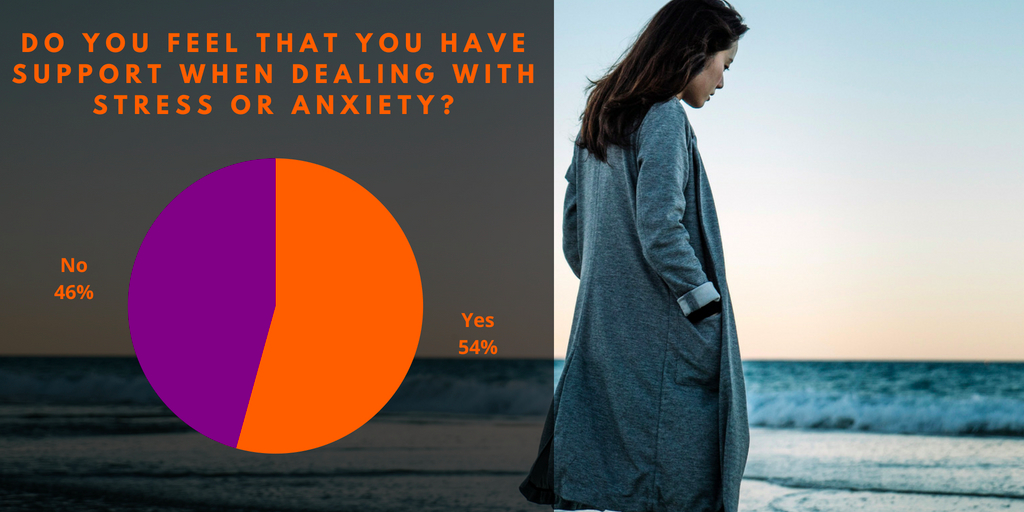

The responses on having support when dealing with stress or anxiety could be viewed as more encouraging. The slight majority feels that they have support. However, 46% state that they lack support, and that is, based on our view, a gap that is much too wide.

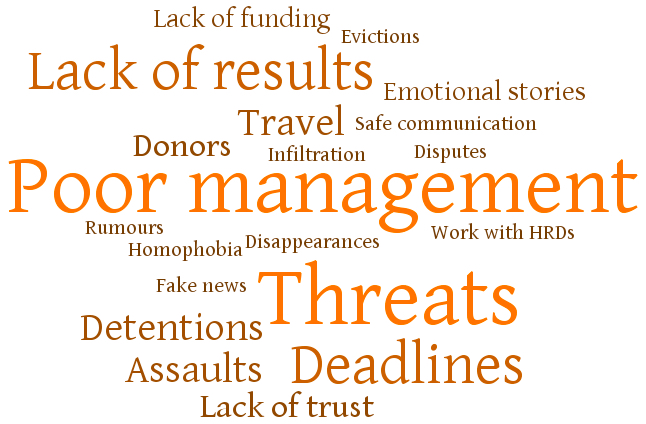

We then went on to ask what if there were any specific situations that increases stress or anxiety for the respondents, and if so, which situations?

We coded their answers into 20 different categories, out of which ‘Poor management’ and ‘Threats’ were the most common. ‘Lack of results’ and ‘Deadlines’ were the second most common reasons for causing stress and anxiety, followed by ‘Assaults’, ‘Detentions’ and ‘Travel’. One could argue that the lack of results and tight deadlines are caused by poor management, as such making it the most common issue. By the same argument, we could group threats, assaults and detentions, under ‘security concerns’, making it the second largest category.

On the upside, poor management, is within the control of the organisation and could thus be affected by better internal policies and processes. This again highlights the important discussion spearheaded by Witness and Physicians for Human Rights to which we referred to above.

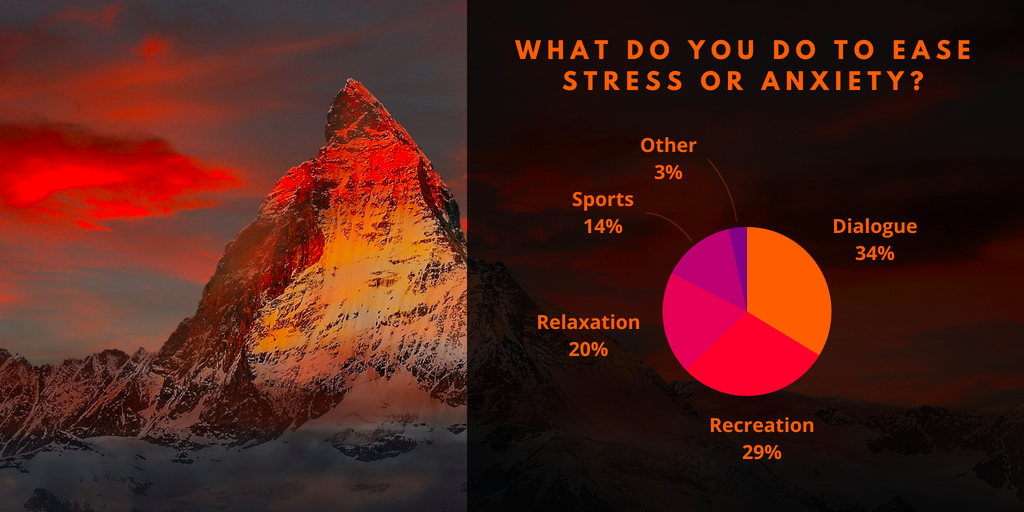

We also asked our partner human rights defenders what they do to ease stress or anxiety. These are some of their answers:

Talking to colleagues and friends was the most common trick to ease stress or anxiety. Coded together, different types of dialogues was the most common, closely followed by different types of recreation. Our trainer, who is also an experienced psychologist, stated that alcohol is probably more common than this survey shows, because people are often hesitant to mention it (even when anonymous). The third largest category was relaxation, in which rest/sleep was by far the most commonly stated coping strategy. We would have hoped to see more than 14 % state sports as their favourite coping mechanism as it is a great way to release stress, release endorphins and build the stamina necessary for future resistance.

Finally, we asked what support they wish to have during times of stress or anxiety.

Most mention that they would want to receive emotional support, particularly mentioning counselling or someone else to talk to. Again, organisational management is an issue, as many wish they would receive more support from management when they are struggling. As often happens the data is interlinked, and therefore hard to code. ‘Time off’ came up several times which is why we coded it as its own category, however an argument can be made to include it in management support. Many also requested practical tips, ideas or trainings to learn techniques — mitigation strategies — for coping with stress or anxiety. Collectively it seems obvious that not enough resources are allocated for long-term emotional security among the human rights defenders that we surveyed.

Towards the end of a session for funders at RightsCon, one of the donors questioned the ethics of supporting human rights defenders financially, but not backing them with other support mechanisms. Essentially, providing funding incentivising the human rights defenders to act, but not having their back should their actions be punished. At Civil Rights Defenders we have a whole toolkit to deal with security holistically.

We work proactively to prevent security breaches by providing trainings on operational and digital security as well as stress management and deescalation. In addition we have the Natalia Project and Emergency Fund that both work to prevent and react on security concerns. Natalia Project sends an alarm when a human rights defenders is in distress and the Emergency Fund allows us to quickly issue money to solve acute situations such as medical bills, relocations or similar. In conjunction to these efforts the Innovation Initiative works directly with human rights defenders to innovate new security solutions based on their needs.

We have also provided trainings on emotional security for quite some time, but based on the survey, other qualitative input from partners and colleagues, as well as the broader discussion in the human rights community about the importance for a more structured approach on emotional security, it seems obvious that we should aim to do even more.

We are therefore currently investigating, together with experts and human rights defenders, how Civil Rights Defenders and the Innovation Initiative could add value. What support could we provide to the human rights defenders we work with? What is most urgent? How can we do this digitally? If you want to be part of the conversation, feel free to contact us.