Where Are We on Digital Rights and How Did We Get Here?

This is the first of three parts of the Innovation Initiative’s special series on digital rights entitled “The State of Digital Rights”. To illustrate the complexity of digital rights we will attack it from three different angles. We start with the rules that govern digital rights, followed by the actors that influence policy, and finally we look at the forums for digital rights practitioners. This is by no means an ultimate guide to the vast area of digital rights, however, we hope it to serve as an introduction to a complex subject.

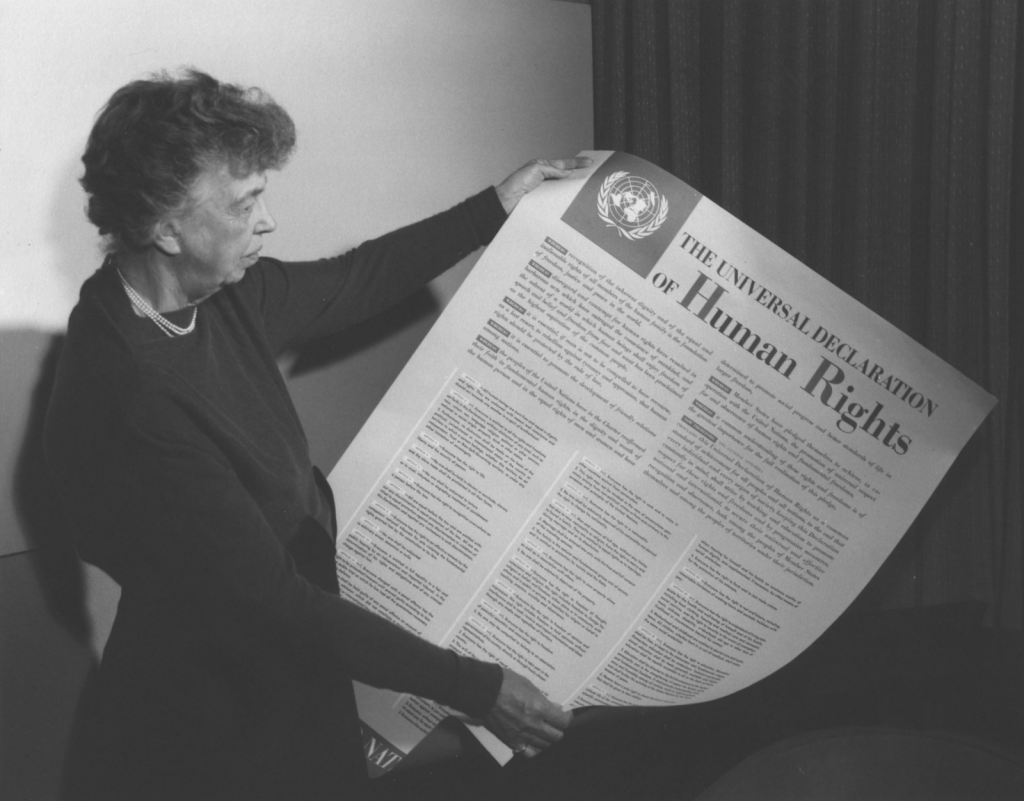

Human rights are international moral norms, which describe standards of human interaction, that are regularly enforced in national and international law. The history of human rights is often described as beginning in 1215 with the Magna Carta and continued with the English Bill of Rights (1689), the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen (1789), and the Bill of Rights in the United States Constitution (1791). Today, international law references the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (United Nations, 1948b) as the cornerstone document of human rights.

The modern age has seen an explosive spread of information and communications technology (ICT). This development has occurred at such a pace that international legal norms and enforcement is having difficulty keeping up. The result has been a considerably unregulated digital landscape where many actors are largely left to conduct their affairs without much regulation. This digital “wild west” has led to unprecedented knowledge aggregation and cross-cultural exchanges. But it has also left many feeling uneasy and wondering whether a digital free-for-all serves to affirm international human rights norms or rather circumvent them.

For evidence of this latter potential, one need only look as far as China. China has recently unveiled beta testing of a social credit system. The system combines social media, credit scoring, and facial recognition software into one monolith. Under this system, citizen’s credit score changes in real time depending on what they do online and in reality. If you like something supported by the government, your score increases. If you do something the government dislikes, then your score decreases. What do citizens use credit scores for? If you have a good credit score, then you will receive automatic upgrades at hotels, better employment opportunities, and better education opportunities for your children. If, however, you have a bad credit score, then you can be barred from promotions or from traveling. The worst case scenario here is that, through this system, a government would become able to dictate ubiquitously and omnipotently how its citizens behave. If a citizen deviates from that prescription, then the government will have the ability to punish that person no matter where they are and without the need to involve law enforcement officers. This new digital tool represents an unprecedented advancement in dictatorial power. It is dystopian to say the least. Without clear identification and strict regulation of digital rights, the international community has little grounds for recourse.

Social media platforms, such as Facebook, Twitter and Google have also taken advantage of ambiguous digital regulation to monetise user data. This process is of course outlined explicitly in their user agreements. The question remains here whether this type of contract is consistent with digital rights. It is not possible for an individual today to sign away his/her human rights. The same should be true of digital rights. But we don’t yet know what they are. The discussion around human rights has yet to map the ambiguous territory of the Internet.

What is clear today is that broad support has amassed behind proposals for certain digital rights. According to a global poll conducted across 26 countries by the BBC, almost four in five Internet users support the idea that access to the Internet ought to be a fundamental human right; and nearly the same percentage claim that access to the Internet has brought them greater freedom. These opinions are echoed by a 2011 report submitted to the Human Rights Council of the United Nations General Assembly by the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression. Recommendation 85 of 88 states, “Given that the Internet has become an indispensable tool for realizing a range of human rights, combating inequality, and accelerating development and human progress, ensuring universal access to the Internet should be a priority for all States.” Though this report does not itself explicitly recommend that access to the Internet ought to be enshrined as a fundamental human right, it does state that the willful restriction of access to the Internet by governments constitutes a restriction of citizen’s human rights.

In support of the global movement typified by this report, several countries are actively pushing for a more clearly legislated enforcement of international human rights norms in the digital sphere. Costa Rica’s Supreme Court has stated that information technology is, “facilitating the connection between people and institutions worldwide”. It called this technology, “a basic tool to facilitate the exercise of fundamental rights”. Estonia’s government has argued that access to the Internet is essential for life in the 21st century. By 2015, Finland’s Ministry of Transport and Communications claimed that every person in Finland was to be guaranteed access to a 100 Mbit/s Internet connection. In 2009, France’s highest court proclaimed that access to the Internet is a basic human right. The Constitution of Greece states that all persons have the right to participate in the Information Society.

These efforts of sovereign nations to protect their own citizens are certainly noteworthy, however, many digital exchanges occur outside of the jurisdiction of individual nations. Should intergovernmental organisations step in to adjudicate this space? To address this point, the World Summit on the Information Society (WSIS) was convened in 2003. Negotiations between governments, businesses, and civil society representatives generated the WSIS Declaration of Principles. Though they contain a number of references to human rights, the principles have been criticised for failing to ensure that human rights are incorporated into practice. In 2008, the Global Network Initiative (GNI) was launched on a foundation of internationally recognised laws and standards for human rights on freedom of expression and privacy. Participants include the Electronic Frontier Foundation, Human Rights Watch, Google, Microsoft, Yahoo and many others. The GNI has been criticised as being toothless. Critics have instead called for participating companies and organisations to embed human rights responsibilities directly into their bylaws.

Today, there remains a considerable amount of work to do in order to secure digital rights. The first step would be to identify what constitutes a digital right. The second step is to develop international enforcement mechanisms necessary to protect digital rights. Significant work has already been conducted in order to cement international norms around certain digital rights. However, legislatively there’s still a chasm between the offline and online world. The digital norms of today have a long way to go to become the hard legal rules that we will need to securely protect human rights online.